Sunday Observance

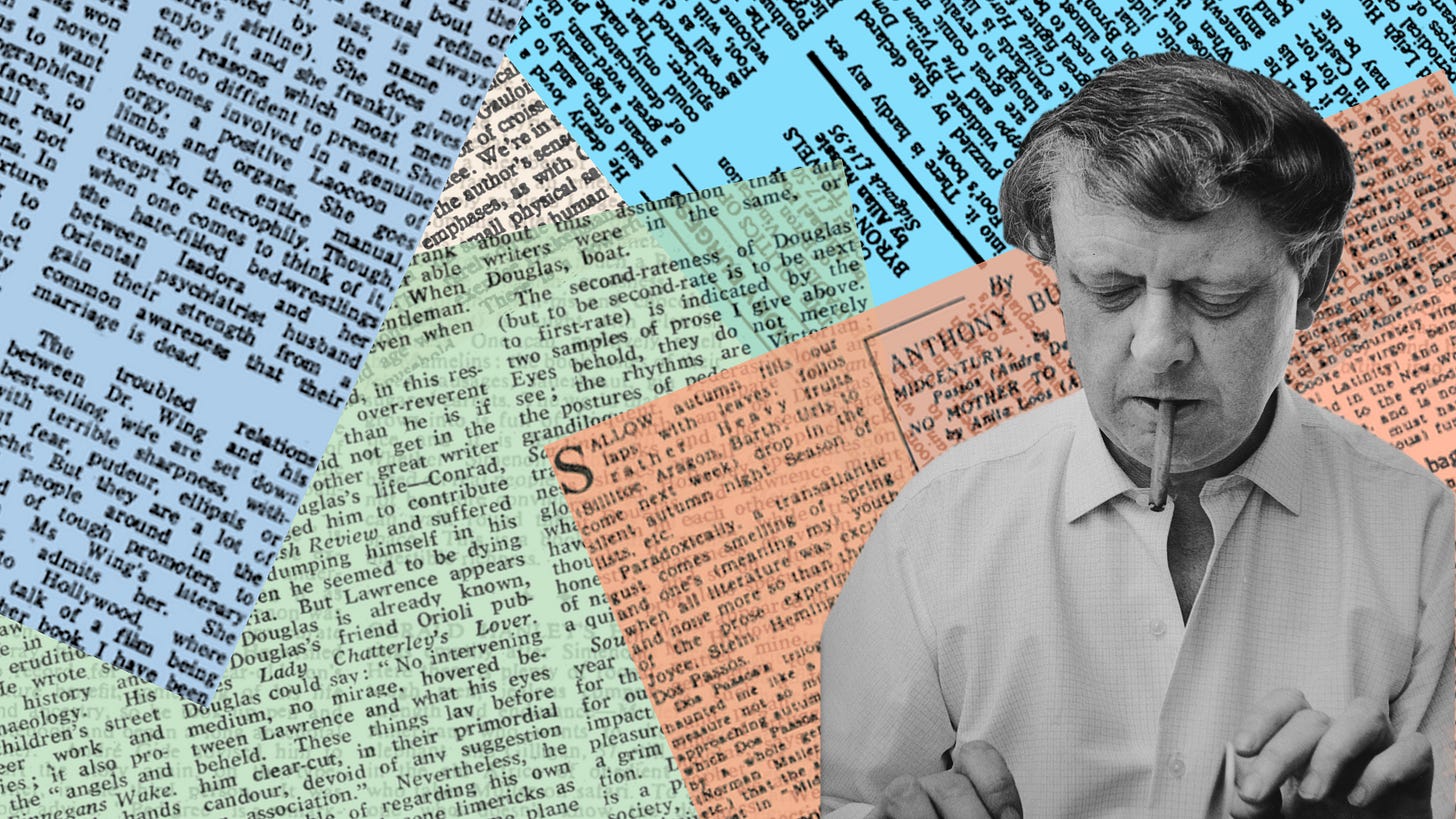

Anthony Burgess as critic in the Observer newspaper

Anthony Burgess’s first appearance in a national newspaper took place in November 1929, when he was just 12 years old. He won a prize of one guinea (or 21 shillings) for submitting a drawing of his father to the Manchester Guardian, which was running an art competition for young people. This was an encouraging start to what became a long career in journalism.

Burgess went on to write for most of the major newspapers in English, French and Italian, including the Times Literary Supplement, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Le Monde, Il Giornale and the Independent. But his most substantial body of journalistic writing was for the Observer, the oldest Sunday newspaper in Britain, founded in 1791.

He contributed around 500 articles to the arts pages of the Observer. His book reviews and author profiles appeared on a regular basis from 1961 until 1993, the year in which he died. If these articles were to be collected in book form, there would be enough material to fill at least ten bulky volumes.

Burgess was hired as a critic by the Observer’s literary editor Terence Kilmartin, himself a considerable man of letters who had single-handedly re-translated Proust’s epic novel. Over time, Burgess rose through the ranks to become the Observer’s chief book reviewer. His work appeared alongside that of other prominent critics, such as Philip Toynbee, Lorna Sage, Philip French and Clive James.

It’s easy to see why his lively articles were valued by editors and readers. Reviewing the letters of Oscar Wilde in the Observer on 8 April 1979, Burgess offers a brisk summary of Wilde as ‘a brilliant young Irishman’ who dazzled the London worlds of art, fashion and literature with his gifts of ‘charm, good nature, wit and creative talent.’ He approaches the book, and the figure of Wilde, with the sympathy of a fellow grafter in the marketplace of paper and ink:

It is pathetic to read his final letter, dated 20 November 1900, written to Frank Harris (a rogue who never really got caught up with). It is about the money Harris owes and which Wilde, whose terminal illness is costing him dear, desperately needs. A great and dying artist is enmeshed in the sordor of debts and bankruptcy laws, sleeplessness over money, literary robbers.

Summing up the collection, Burgess claims that Wilde transformed letter-writing into an art-form. Arguing the case for letters as an under-valued literary genre, he writes: ‘This book must be cherished and not allowed to go out of print.’

On other occasions, we can see Burgess using his own experience to illustrate how times have changed. Reviewing a memoir of Joseph Conrad, he writes:

I shopped in the supermarket, dragged three bags up three flights, peeled potatoes, cleaned Brussels sprouts, put the joint in the oven, washed yesterday’s dishes, made the beds, swept the floors, then sat down to Mr Conrad’s reminiscences of life at the house called Oswalds.

Comparing his life with that of Joseph Conrad, who was ‘not a rich author’, Burgess notes that, in 1914, Conrad could afford to employ a butler, two housemaids, a cook, two full-time gardeners, a chauffeur, and a nurse for his wife Jessie. ‘One cannot help a breath of envy,’ writes Burgess, whose wife and son were less than dynamic when it came to helping out with the housework.

Nevertheless, his hard work as a journalist brought some financial rewards. According to Blake Morrison, who commissioned Burgess’s reviews for the Observer in the 1980s, he was paid £600 for each thousand-word piece. He was a beneficiary of what now looks like a golden age, when writers were handsomely rewarded for their copy. An incipient literary journalist today would be lucky to earn a third of that amount.

Despite the hardships of the professional writer’s life, which he wasn’t slow to grumble about, Burgess believed that journalism was still a noble enterprise. It brought his work to the attention of many readers who had probably never opened a literary novel, and it allowed his voice as a writer, always energetic and engaging, to gain a much wider readership.

Burgess’s journalism is currently available in two volumes of essays: The Ink Trade, a selection of book reviews, and The Devil Prefers Mozart, a compendium of his essays on music. Both books are published by Carcanet.

His long association with the Observer is commemorated by the Observer Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism, an annual writing competition which aims to find the best new voices in cultural criticism.

Entrants are asked to submit a review of 800 words on a new piece of culture which has appeared since the beginning of 2025. The closing date for entries is 28 February 2026.

Find out more

For terms and conditions, entry criteria, and useful tips for your writing, visit the Observer Anthony Burgess Prize pages on our website.

For inspiration, why not read the work of previous winners and runners-up?

2013-2024 winners at the Guardian online (formerly home to the Observer).

Read Blake Morrison on Anthony Burgess as critic.

Buy The Ink Trade: Selected Journalism by Anthony Burgess (affiliate link).

Buy The Devil Prefers Mozart: Essays on Music by Anthony Burgess (affiliate link).

Buying books from the Burgess Foundation’s affiliate bookshop (powered by Bookshop.org) supports our charitable work.

Fascinating documetation of what sustained literary output actually looked like. The contrast between Conrad's household staff and Burgess juggling groceries is revealing not just economically but creatively. When critical writing paid £600 per 1000 words (adjusted for inflation thats substantial), it meant criticism could be a primary occupation rather than a side hustle. I actualy think the 500-article corpus might be more culturaly significant than some novelists' entire careers.