From Byron to Byrne

200 years after the death of Lord Byron, we examine Anthony Burgess’s responses to the poet’s work

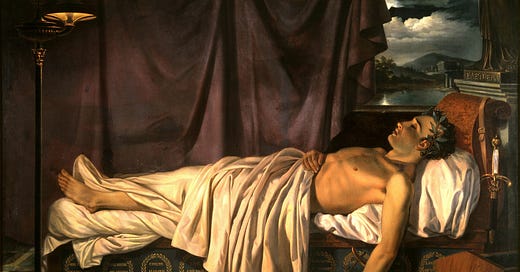

When George Gordon, the sixth Lord Byron, died in Missolonghi in 1824, his reputation as a military hero was already secure among the Greek soldiers he had led in the war of independence. He is better known to the rest of the world as one of the three poets who defined the first wave of the Romantic movement in Britain.

Unlike John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Byron’s poetic reputation has always been truly international – but the three poets were united by having met early deaths.‘The romantic spirit,’ Anthony Burgess wrote, ‘is best exemplified by youth, and indeed it was in the work of men who died when they were still young that the peculiar youthfulness – or, if you will, immaturity – of romanticism found its most typical voice.’

Burgess often writes about the first wave of Romantic poets in his journalism, and the image of Byron that emerges from his criticism is typically bold, focusing on his reputation for manliness and unconventional behaviour. This is how Burgess introduces Byron in They Wrote in English, a volume of literary history:

It may be that his personality got in the way of his literary merits, and the glamour of the man was attached to the work. He became, as we know, a legend in his own time – the cynic of immense handsomeness, cricketer, boxer, swimmer who swam the Hellespont like Leander, careless lover, debauchee and atheist. Egocentric in literature as well as in his social conduct, he made himself the hero of his own poems.

This is typical of how Byron is characterised in the popular imagination, but his physical adventures, macho exploits and heroic legacy often stand at odds with his art. Although Burgess says that the poetry betrays a ‘cavalier carelessness’ – Byron boasted that he could compose a rhyming stanza in just 30 seconds – he goes on to say that Byron ‘is one of the romantics in whom a classical element is strong, with a concomitant talent for the cerebral, the pithy, the epigrammatic.’

For Burgess, the heroic-epic poem Don Juan was Byron’s greatest achievement, though critics continue to argue about whether or not the poem is finished. Byron reworks the old European legend of Don John or Don Giovanni, traditionally seen as a libertine seducer. In Byron’s version he is a luckless innocent who becomes enslaved, fails at love, and goes on to pursue seemingly endless bedroom adventures. The poem’s opening canto pokes fun at Byron’s contemporaries: the Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, is ‘disappointed in [his] wish / To supersede all warblers here below’; Samuel Taylor Coleridge is ‘a hawk encumber’d with his hood’; William Wordsworth writes poetry ‘at least by his assertion’; and the group of poets based in the Lake District would do better, in Byron’s opinion, to ‘change [their] lakes for Oceans.’

Don Juan was not simply a poem that Burgess admired: it was also an influence on his own creative work. In the early 1970s, he planned an uncompleted Broadway musical based on Don Juan. Some song lyrics intended for this show have survived in a notebook:

Sevilla, Seviya, Sevija – or Seville.

Call it what you will

It’s the same town,

Not a tame town – no shame at all.

They’re waiting for the moonlight to fall

On Sevilla, Seviya, Sevija – or Seville.

Come here when you will.

Crane your necks at

All the sex at your beck and call.

Romantic writers appear elsewhere in Burgess’s fiction: the story of Byron’s meeting with Percy and Mary Shelley at the Villa Diodati near Geneva forms the basis of Ronald Beard’s Frankenstein film script in Beard’s Roman Women; and ABBA ABBA explores the final days of Keats in Rome, where he has a fictional meeting with the Romanesco poet Belli.

Byron’s influence is felt most keenly in Burgess’s posthumously-published novel-in-verse, Byrne, written in the same poetic form that Byron used for Don Juan. Ottava rima is a style associated with Ludovico Ariosto’s long Italian poem Orlando Furioiso, and it was later deployed in mock-heroic poetry.

Burgess’s novel follows the adventures of a twentieth-century Don Juan character, Michael Byrne, an Irishman of Spanish descent who travels the world working as a painter, poet and composer, fathering many children along the way. The wayward Byrne is eventually confronted by his offspring in the novel’s explosive finale.

Burgess’s debt to Byron is clearly signposted in the opening section of Byrne:

He thought he was a kind of living myth

And hence deserving of ottava rima,

The scheme that Ariosto juggled with,

Apt for a lecherous defective dreamer.

He’d have preferred a stronger-muscled smith,

Anvilling rhymes amid poetic steam, a

Sort of Lord Byron. Byron was long dead.

This poetaster had to do instead.

The library of books owned by Burgess at the Foundation in Manchester includes a copy of the Oxford Authors edition of Byron’s works, containing a note written by his wife, Liana. She states that Burgess was reading this book while he was writing Byrne. The editor of the volume was John D. Jump, who taught Romantic poetry when Burgess was studying English at Manchester University in the 1930s.

As with any larger-than-life character who lives a life of freedom and adventure, it is perhaps natural for readers to be seduced by the image of Byron as a romantic rake. Burgess notes that Byron’s poetry was always more highly valued in Europe than in Britain, and he suggests that the British could not overlook the scandals of his life.

Burgess takes a broad and rounded view of Byron the poet and the man. Of the poet, he writes, ‘Don Juan, Beppo and The Vision of Judgement are great comic masterpieces, though no revaluation of poetic standards is likely to rehabilitate Childe Harold.’ And of the man: ‘he was a nobleman […] and one of the rare figures of history who gives honour to his rank. Mr Gordon might not so effectually have enflamed the world.’

Find out more

Listen to Anthony Burgess reading ‘She Walks in Beauty’ by Lord Byron:

Fascinating. I'd like to know more about AB's musical version of Don Juan: how far did he get with the project?

One small correction: "Byrne" does start in ottava rima, but then halfway through it shifts to Spenserian stanzas, for, I would say, no very good reason.