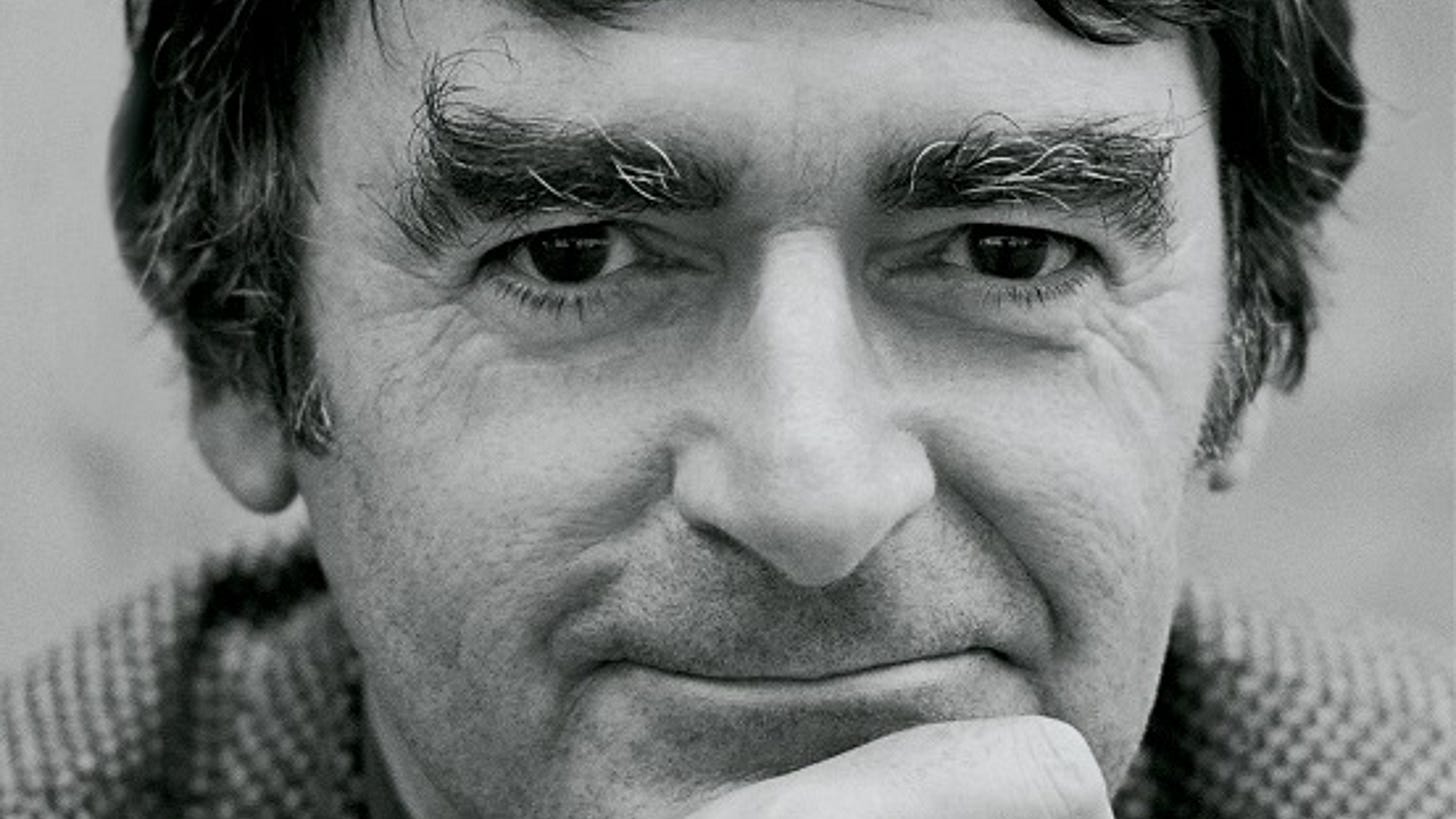

David Lodge (1935-2025)

Remembering the novelist, literary critic, pioneer of campus fiction, and patron of the Anthony Burgess Foundation.

David Lodge’s witty and insightful novels about academic life earned him the devotion of his readers and turned him into a literary celebrity. Along with writers such as Malcolm Bradbury and Angus Wilson, he helped pioneer the post-war campus novel in Britain, a genre which reached its peak in the 1980s with television adaptations of Bradbury’s The History Man and Lodge’s Small World and Nice Work.

Away from his fiction, Lodge was an active academic, primarily at the University of Birmingham, with which he was associated between 1960 and 1987. His books of literary criticism became familiar to students of literature and many of them, such as The Art of Fiction (1992), gained popularity outside the academy. This book contains an essay which analyses Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange.

Burgess often praised Lodge’s novels, identifying him as ‘one of the best novelists of his generation’. The two writers became friends, first meeting in Rome in 1974. Burgess included Lodge’s novel How Far Can you Go? in Ninety-Nine Novels, his selection of favourite novels of the mid-twentieth century. In his review of the novel, Burgess notes Lodge’s ‘high moral seriousness underneath the flippancy.’ For his part, Lodge arranged for Burgess to be awarded an honorary doctorate by Birmingham University in 1986.

After Burgess died in 1993, Lodge often corresponded with his widow, Liana, who set up the Burgess Foundation in 2003. She invited Lodge to be an honorary patron of the Foundation, and he accepted, continuing in this role until 2025.

To remember David Lodge, here is Burgess’s review of Nice Work, originally published in the Observer on 18 September 1988. Burgess argues that Lodge was working in the tradition of Charles Dickens, another writer he very much admired.

‘Coketown in the 1980s’ by Anthony Burgess

Nice work, indeed; a very nice work. Or rather a work of immense intelligence, informative, disturbing and diverting. Etymologically speaking, nice is inept, coming from the Latin nescius, which means ignorant. God knows how this meliorative change has happened.

On the other hand, David Lodge's two main characters work in ignorance of the work of each other: Victor Wilcox, managing director of a firm that makes metal components for other firms, and Robyn Penrose, temporary lecturer in English Literature at the University of Rummidge. The narrative is about how, following a directive to bring industry and academia closer together, the two disparate disciplines, thesis and antithesis, meet, struggle, and then achieve a kind of synthesis in bed. But it is also about much more.

Devoted readers of Mr Lodge will be glad to see that he has not deserted the University of Rummidge. Old friends like Philip Swallow appear, and Morris Zapp of the University of Euphoria irrupts before the end, a deus ex machina. Zapp has gained rather than lost ebullience, but Philip’s philandering days are over and he has gone deaf. As Dean of the faculty, he has to worry about Thatcherian cuts, but not so much as Robyn, who fears she will never attain tenure. She is a bright pretty girl of Australian origin who lectures about the ogre of industry in the English nineteenth-century novel, the thrusting phalloid ravisher of pastoral content. She also does a course in literary feminism. And, very up-to-date, she knows all about semiology.

If she is willing to go as a weekly ‘shadow’ to Vic Wilcox, this is partly so that she can, though fiercely independent, enhance her chances of gaining tenure. Like the hero of Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, she enters hell. Mr Lodge has done his homework on Rummidge substructure, and furnaces, filth, unemployment, smashed factory windows, abandoned factory shells, what looks to appalled Robyn like the Victorian nightmare enshrined in Sybil and Hard Times, all hit us with powerful authenticity.

But all her doctrinaire diatribes bounce from the rusty metal of Vic’s pragmatism. Late capitalism? What the hell is she talking about? Slavery? Black unemployed fight each other for the privilege of unionised agony. There’s no chained-down nobility in the workers, who are mostly a filthy lot and vandalise the newly installed lavatories. Robyn foments a small strike and then has to humiliate herself in apology to get it stopped. Small talk in Vic’s Jaguar about the semiology of a Silk Cut advertisement seems to bounce back from a metallurgist’s common sense, but Vic, to his astonishment, finds himself falling in love with Robyn.

This is far from implausible. Vic is bored with his fat wife, who reads in bed a book called Enjoy Your Menopause, with his punkish daughter and dropout, layabout son. Robyn is bright, she can talk, she has ready repartee. She knows German and, on a business trip to Frankfurt to buy German machinery, she finds out that Vic is to be cheated. There is an interface between academia and industry; and it is linguistic. It will not be long before Vic sees sense in semiology. Meanwhile, in the Frankfurt hotel with its jacuzzi and minibar, Vic’s love is consummated.

Small World frankly and enjoyably exploited the conventions of romance. Nice Work accepts the neatness of surprises in the denouement, ends tied nicely but not too nicely. Vic, in a takeover, loses his job, and this promotes the recovery of solidarity in his family. Zapp, impressed by the print-out of Robyn's word-processed book, asks her to fax her CV to Euphoria in preparation for a well-paid post. But the unknown word virement, which has appeared in interdepartmental memos and puzzled Philip Swallow, suddenly discloses its meaning and the possibility of tenure for Robyn at Rummidge. She decides to stay on. There is, after all, a future in Britain.

But the Thatcherian present looks pretty grim, what with girl students paying their way through their courses posing in underwear and delivering kissograms, Disraeli's 'two nations' still confronting, or ignoring, each other, the wreck of an empire manifested in jobless layabouts with ear-splitting amplifying systems. And what does metonymy or aporia mean to 99.9 per cent of Rummidge's population?

The book could be dour, but it is not. It is not hopeful, but it is too entertaining to leave a sour taste. It is what was once called a Condition-of-England novel but there is no Victorian heaviness in it. Rather, the prose dances and, being the very modern medium of a structuralist, it occasionally takes sly peeps at itself in the mirror.

The book confirms David Lodge's right to be taken very seriously indeed as one of the best novelists of his generation, and, if some will regard it as 'too British,' what else should a British writer produce? Dickens was all too British too.

Find out more

Read David Lodge’s memories of Anthony Burgess, written in 2017.

Listen to the Ninety-Nine Novels episode on The History Man by Malcolm Bradbury, another pioneer of the post-war campus novel: