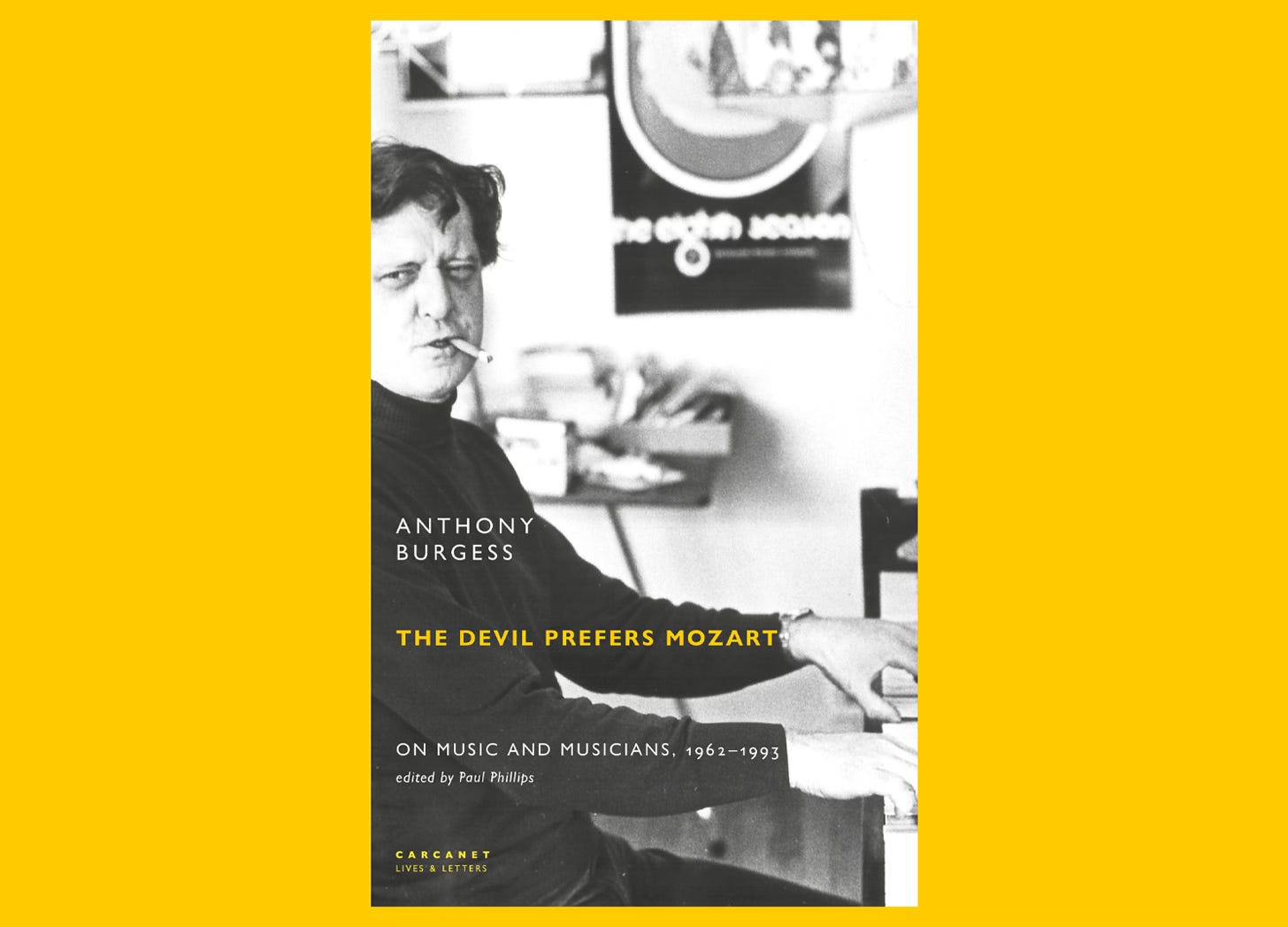

Anthony Burgess: The Devil Prefers Mozart

We introduce a new book of essays, The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians, with a brief history of Anthony Burgess’s musical life, and an outline of what to expect from the book.

A Musical Life

Music surrounded Anthony Burgess throughout his early years in Manchester. He came from a family of musicians: his mother had been a music-hall singer, and his father played piano in pubs, music halls and silent cinemas.

In his book about music and literature, This Man and Music, Burgess says his father was never a professional pianist, but in his spare time played piano in pubs, such as the Golden Eagle in north Manchester. Burgess lived above this pub after his father married the landlady in 1922. It was a rowdy establishment, and Burgess remembers three pianos in the downstairs bars, which ‘thumped and tinkled simultaneously, like something by Charles Ives [the American experimental composer]’. He writes that his parents gave him an ‘ancestral memory of the music hall and the actuality of much popular music’.

When he was a schoolboy, Burgess built a crystal radio set in his bedroom so that he could listen to dance music. By accident he tuned into a broadcast of Claude Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune – and he looked back on this moment as a life-changing encounter with modern music.

A deeper immersion in classical music followed. From 1929, when he was 12 years old, Burgess and his father held season tickets for the Hallé Orchestra, and they regularly attended their Thursday evening concerts at the Free Trade Hall on Peter Street, Manchester. They were in the audience for the world premiere of Constant Lambert’s jazz-inspired work The Rio Grande, which influenced Burgess’s own later compositions.

Although he retained his love of popular music and jazz standards, he came to love classical composers such as Wagner, Beethoven, Holst, Stravinsky, Elgar, Walton and Shostakovich.

According to his two volumes of autobiography, Burgess wrote music at every stage in his life. He claimed to have composed a symphony in 1935, when he was eighteen, but the score is not present in any of the Burgess archives. His earliest surviving composition is the Sonata for Violincello and Piano in G Minor, written in Gibraltar in 1945 and containing several hallmarks of his music, such as pungent tonality, angular melodies and quartal sonorities.

When he was teaching in South-East Asia, he wrote the words and music for a Jubilee Anthem for Malayan Boys’ Voices for the 50th anniversary of Malay College in Kuala Kangsar. Former students at the college have strong memories of performing this song in 1954.

Once Burgess became widely known as a writer, he found opportunities for his music to be performed on a larger scale. The turning point was a performance of his Symphony in C in Iowa in 1975. The success of this work gave him confidence to write more music, and by the time of his death in 1993 he had completed around 250 compositions, including chamber works, stage musicals, a piano concerto and a violin concerto written for Yehudi Menuhin.

Readers of Burgess’s novels will already be aware that music plays a central role in many of his novels, such as Napoleon Symphony, Mozart and the Wolf Gang and A Clockwork Orange, in which Alex listens to Beethoven before going out to commit acts of ultra-violence.

Burgess’s work as a music critic is documented in two non-fiction books: This Man and Music and Homage to Qwert Yuiop. The existing picture is widened and deepened by the publication of a new selection of Burgess’s essays on music in January 2024.

The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians

In this flavoursome and entertaining collection of writings about music, Burgess reflects on the classical canon – with reference to Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, Delius – and gives us strong opinions on twentieth-century practitioners, such as Stravinsky, Elgar, and The Beatles.

Despite his reputation as the ‘Godfather of Punk’ – bestowed by the New York Times following the release of Stanley Kubrick’s film version of A Clockwork Orange – Burgess is unexpectedly severe in his writing about Sid Vicious and The Sex Pistols.

Another section of the book focuses on opera, with extended essays on Mozart, Wagner, Benjamin Britten, Georges Bizet, and Burgess’s own opera libretti.

He provides an insider’s view of how music is made when he reflects on his own compositions for symphony orchestra, piano and guitar.

The Devil Prefers Mozart demonstrates the versatility of Burgess’s non-fiction writing and confirms the extent to which music was always at the heart of his creative life.

The collection includes many pieces which have not previously appeared in book form, such as talks originally broadcast on BBC radio and articles written for publication in French and Italian journals.

Burgess often said that he thought of himself as a musician who happened to be a novelist. The Devil Prefers Mozart allows us to see the full range of his musical interests, both as a critic and as a composer. As you would expect from Burgess, these essays are written with the energy and panache that we associate with the best of his fiction.

The Devil Prefers Mozart is edited by Paul Phillips, author of a previous book about Burgess’s music, The Clockwork Counterpoint. He is also the director of Orchestral Studies at Stanford University.

Special Offer

The Devil Prefers Mozart will be published on 25 January 2024. Carcanet are offering a pre-order discount of 25% for readers of Anthony Burgess News. To claim your discount, simply input the code IABFDPM25 at the Carcanet online store (offer ends 25 January 2024).

Carcanet also publish The Ink Trade, a selection of Anthony Burgess’s literary essays.

Further Reading: Anthony Burgess on Music

This Man and Music: The Irwell Edition, edited by Christine Lee Gengaro

Mozart and the Wolf Gang: The Irwell Edition, edited by Alan Shockley