Anthony Burgess on the music of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Burgess considers the legacy of the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. An extract from The Devil Prefers Mozart, a new collection of his essays on music.

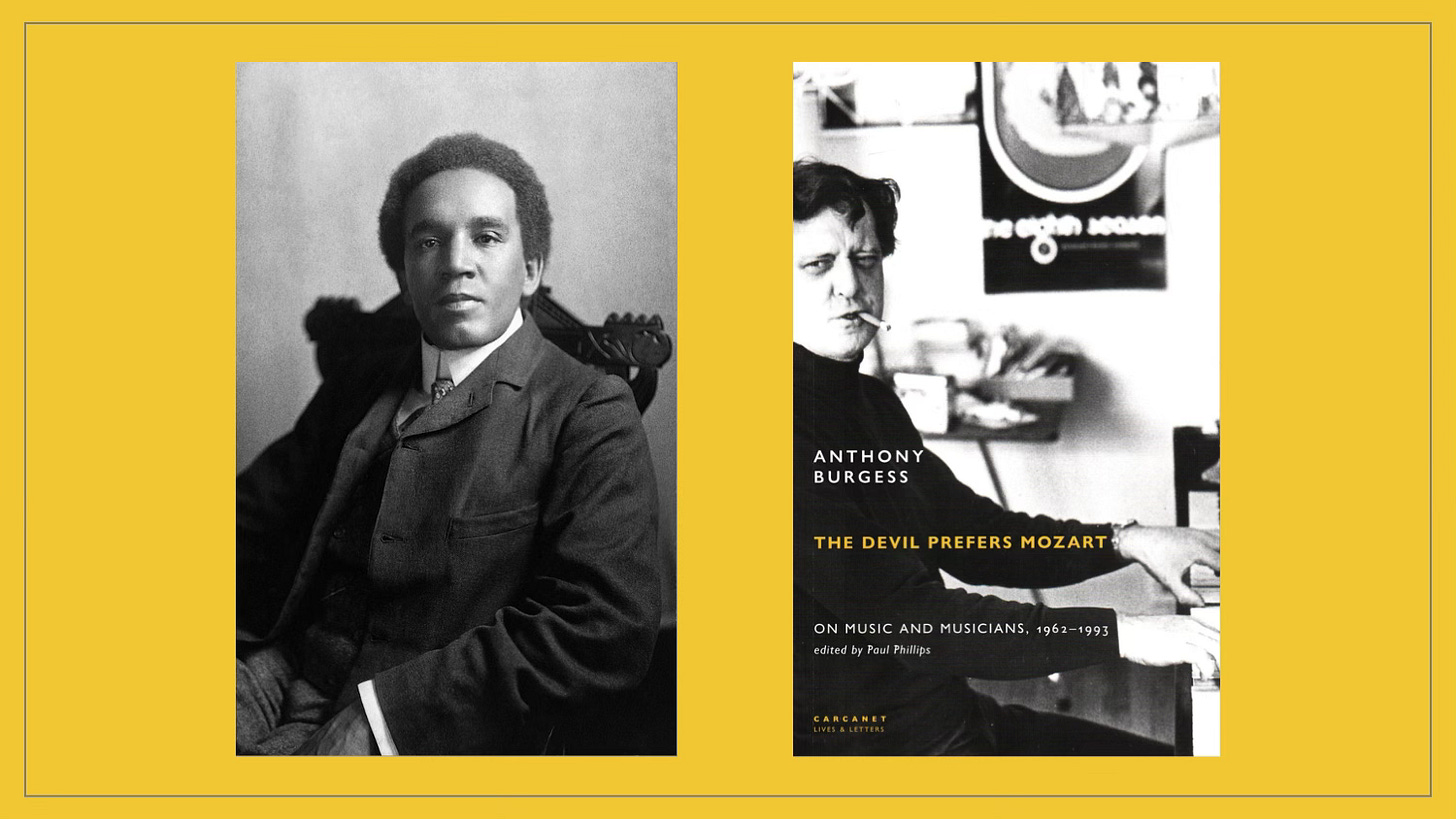

The Devil Prefers Mozart is the first collection of Anthony Burgess’s essays on music and musicians. Edited by Paul Phillips, this wide-ranging anthology covers classical, modern and operatic works, including jazz, pop and punk.

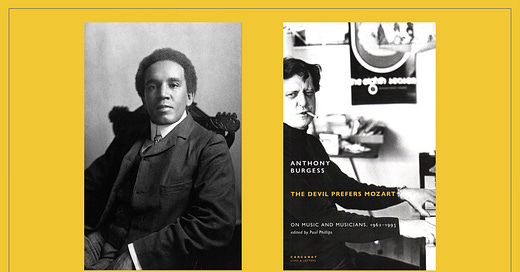

In this extract, Burgess writes about Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), a popular British composer of mixed heritage, known in his lifetime as ‘the African Mahler’. His music gained the attention of Edward Elgar, who described him as ‘far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the younger men.’ His settings of Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha were so popular that they led to a tour of the US and a meeting with Theodore Roosevelt at the White House. When Coleridge-Taylor died at the age of 37, he was honoured by King George V and a memorial concert at the Royal Albert Hall.

The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians is available now in the UK, and from 28 March in the United States. We are offering a 25% discount to readers of Anthony Burgess News (see below).

‘In Tune with the Popular Soul’

Times Literary Supplement, 15 February 1980

A review of Avril Coleridge-Taylor, The Heritage of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (London: Dobson, 1979)

I knew Samuel Coleridge-Taylor before I knew Samuel Taylor Coleridge. My father strummed the ‘Petite Suite de Concert’ on the piano. Pier bands would play the Othello suite. I was taken to hear the choirs of mills and factories perform Hiawatha. Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s citation of the opening bars of the Ballade for orchestra brings back vividly the experience, in my adolescence, of hearing it live — probably conducted by Sir God Damfrey, as Peter Warlock called him, at Bournemouth.

Coleridge-Taylor was a part of popular British musical life and Hiawatha still lives on, as solid an annual ceremony as Messiah. His daughter recalls hearing a blues version of ‘Demande et Réponse’ belting out of a London railway terminus public address system. That would be ‘Question and Answer’, a popular waltz I well remember playing at army dances. Coleridge-Taylor is far from forgotten, but he is not, I think, represented any more in serious orchestral concerts. Sir Arthur Sullivan and Sir Edward Elgar proclaimed his genius, which was a genuine one, but it was not a genius of an order that could produce either a Mikado or a Dream of Gerontius. Although his musical aims could not have been more different, Coleridge-Taylor’s status is probably equivalent to that of George Gershwin. He was a natural melodist with no great gift of Beethovenian development; he was a highly competent colourist; he could appeal to the popular soul.

I learn now for the first time why he was named as he was. His father was Daniel Taylor, who came from the Gold Coast to England to qualify in medicine, duly qualified, grew disgusted with the colour prejudice of patients in the practice in which he was an assistant, and left for Sierra Leone and biographical silence. He left behind in England an English wife, Alice Holmans, and a son of his own colour. This son had been born in the Lake District, and a sentimental association with the Lake Poets got him his name, not at first hyphenated. Coleridge-Taylor was later to make a cantata out of ‘Kubla Khan’, but the music could not rise to the words. He also set some minor lyrics of his namesake, but the songs are no longer sung. It is typical of Coleridge-Taylor’s genius that it could cope with the simple trochees of Longfellow but not with more exalted verses. The list of his songs that his daughter gives us shows that he was typical of the British musicians of his age in having little literary taste. Elgar was no better until some angel led him to Newman. It was only when Holst, Vaughan Williams and Delius discovered Walt Whitman that British choral music found its voice. The Victorian and Edwardian annals of provincial choral festivals make, from the aspect of libretti, distressful reading. Coleridge-Taylor spent two years on an opera that was doomed to silence because of its words. No British musician can afford to neglect his literary heritage, but too many alumni of the Royal College of Music were content with the effusions of provincial journalists who fancied themselves to be poets.

Coleridge-Taylor got to the Royal College having been observed by a kindly musician playing marbles with a violin case under his arm. A little black boy with a fiddle, remarkable. The talent was undoubted and it flourished early. Coleridge-Taylor was only thirty-eight when he died, but he left behind a lot of music. We should, perhaps, regretting that he never moved out of the Brahms-Dvorak orbit that Stanford kept spinning at the RCM, remember that he died in 1912, before he could absorb acerb and ironic impulses from the Continent, and that it was in order for a musician of his period to be content with harmonies that Stainer blessed. But consider that Dvorak, in his New World Symphony, dared consecutive sevenths and chords a tritone apart. Consider too that in 1909 Vaughan Williams set Housman in On Wenlock Edge and effected a quiet tonal and harmonic revolution considered by the late Hubert Foss to be quite as significant as that of Debussy’s Images.

Coleridge-Taylor, subjected to racial slurs in the streets and even from a jealous fellow-student, was a pioneer in the promotion of black rights and black art: he set negro melodies in the style of Dvorak; how much better if he had set them in the style of Vaughan Williams. There are black dances among his works, and an overture dedicated to Toussaint L’Ouverture, but he took no lessons in orchestral and harmonic colour from other British composers who could best teach him about the recovery of ancient styles and the development of exotic ones.

He is limited, then. There is hardly a sound in his works that you will not find in Brahms: Tristan, let alone Debussy, is too modern for him. But the melodic gift is remarkable. Amateur choruses, which like to enjoy their hobby and not serve progressive art with the Gurrelieder, find Hiawatha singable and the telling of the Algonquinian tale, however trivialized by Longfellow, dramatically moving. To produce genuinely popular music on a large scale is given to few. But expectations were different at the Royal College, when Holst merely played the trombone and Vaughan Williams the triangle in one of Coleridge-Taylor’s youthful orchestral works. He was the hope of the British musical future, which meant he would carry the banner of a Central European art already outmoded by Richard Strauss and Mahler.

Avril Coleridge-Taylor — as on a larger scale, Imogen Holst — has divided her life between the exploitation of her father’s music and the creation of music of her own. She gives a list of her works, but if I do not know any of them the fault must lie either in their quality or the crassness of concert promoters. Her life as an orchestral conductor, particularly of Hiawatha, has been distinguished by a residual sadness.

The daughter of a white woman (not, to judge from these pages, at all an exemplary mother) and a man half-black, she was destined to attain her greatest successes in South Africa until the whispers and threats began. It says much for her generosity of spirit that she loves that country. It is hoped that, stimulated by her advocacy of her father’s neglected works (not so much neglected in America, one is glad to see), and intrigued by her admirable technical analyses of some of them, British conductors and chamber groups will consider bringing them back into the repertory.

Benjamin Britten said in 1975: ‘The gift of music which Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born with is something to be remembered with gratitude.’ Sir Malcolm Sargent asked, for a seventieth birthday present, that he be allowed to conduct a full-scale performance of Hiawatha. These are sizable tributes. For my part, I should like to hear again that orchestral Ballade which once, when I was in short trousers in Bournemouth, made me thrill to the possibilities of orchestral colour. When I went back to school after the vacation we read The Ancient Mariner. I had no doubt that the black man had produced better art. Then, alas, I began to grow up.

The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians is available now in the UK, and from 28 March 2024 in the United States.

Carcanet are offering a 25% discount at their web store. Use the code IABFDPM25 at the checkout (offer ends 15 April 2024).

Find out more

‘Ballade for orchestra’, opus 33, by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra plays Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘Hiawatha Overture’ from The Song of Hiawatha.