A Psychologist Skinned

Anthony Burgess questions the utopian ideas of B.F. Skinner

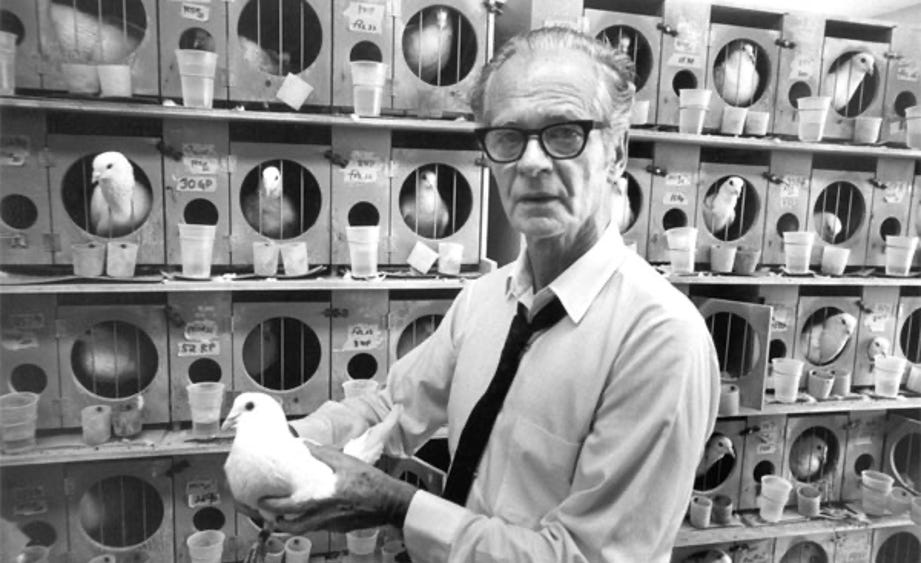

One of the most interesting utopian novels in the Anthony Burgess Foundation’s book collection is Walden Two by the psychologist B.F. Skinner, who was one of the pioneers of behaviourism. Burrhus Frederic Skinner was a Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, and his novel, first published in 1948, is a utopian manifesto in the polemical tradition of Thomas More and William Morris.

Although it takes the form of a novel, Walden Two is mostly concerned with outlining and describing Skinner’s ideal society. Within the frame of fiction, the main characters are guided around the Walden Two experimental community by one of its leaders, a man called Frazier, who is clearly the author’s mouthpiece within the text.

Attempting to create a better society, a group of men and women have opted out of the modern world and set up a commune where there is no crime and everyone can be happy. There is no class system, fashion, advertising or alcohol in this utopia. Members of the community work only four hours a day, and money has been replaced by ‘labor-credits’, with extra credits being available for unpleasant jobs such as cleaning out the sewers. The raising and education of children is undertaken by the community, and the word ‘mother’ has been abolished.

Burgess was horrified by what he found in the pages of Skinner’s utopia. He had first encountered behaviourism in the late 1950s, while he was reading widely in utopian and dystopian fiction, and preparing to write A Clockwork Orange. One of the books he consulted was Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World Revisited. Huxley provided a summary of Science and Human Behavior (1953), the non-fiction book in which Skinner developed his theory that there is no such thing as human nature, and that environment determines everything. To Burgess, who believed in the primacy of free will and individual choice, these ideas were objectionable. One of his aims in A Clockwork Orange was to set out the counter-arguments in favour of laissez-faire politics and free will.

Another book by Skinner, provocatively titled Beyond Freedom and Dignity, appeared in 1971, a few months before the release of Stanley Kubrick’s film version of A Clockwork Orange. This was Skinner’s attempt to popularise his theories in a short book aimed at the mass market. Declaring himself to be against ‘the literature of freedom’, he wrote that the next step in social evolution was ‘not to free men from control but to analyze and change the kinds of control to which they are exposed.’ Given the right environment and a willingness to abandon traditional notions of freedom, Skinner claims, utopia might become a reality for everyone.

The thematic connection with A Clockwork Orange was obvious to many readers of Beyond Freedom and Dignity. Interviewed by Rolling Stone magazine, Kubrick said: ‘I like to believe that Skinner is wrong and that what is sinister is that this philosophy may serve as the basis for some kind of scientifically oriented repressive government.’ He added: ‘I like to believe that there are certain aspects of the human personality which are essentially unique and mysterious.’

Burgess attacked Skinner’s ideas in three notable works of the 1970s. The first of these was a short story, ‘A Fable for Social Scientists’, published in Horizon magazine in 1973. Set in the future, the story is a dialogue between three students who accidentally discover Skinner’s burial site. They talk dismissively about Walden Two and Beyond Freedom and Dignity before speculating about the possible meaning of the initials ‘B.F.’ (‘Bloody Fool’ seems to be Burgess’s preferred answer). Echoing the central message of A Clockwork Orange, one of the characters says: ‘Freedom only matters in this area of choosing between good and evil, and that comes down, I suppose, to choosing not to do evil.’

The next encounter with Skinner may be found in The Clockwork Testament, published in 1974. This novel features a fiery confrontation in a television studio between the poet F.X. Enderby and an academic psychologist called Professor Balaglas, who closely resembles Professor Skinner. Burgess is unsparing in his criticism of Skinner for rejecting ideas such as free will and the autonomous individual who is not conditioned by their environment. Balaglas, speaking the language of Skinner, says: ‘Man is much more than a dog, but like a dog he is within range of a scientific analysis.’ To which Enderby replies: ‘Man was always violent and always sinful and always will be. He won’t change, not unless he becomes something else.’

Burgess resumed the attack on Skinner in his hybrid book 1985, half novella and half critical work about Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. In the critical section Burgess writes: ‘We hear less of Pavlovianism these days than of Skinnerism […] To consider hypnopaedia, or sleep-teaching, cradle conditioning, adolescent reflex bending, and the rest of the behavioural armoury, is to be appalled at the loss of individual liberty.’ Once again, the main targets of his criticism are Walden Two and Beyond Freedom and Dignity.

It’s worth pointing out that Skinner’s proposed methods of social control bear no resemblance to the Ludovico treatment undergone by Alex in A Clockwork Orange. ‘Positive reinforcement’ was at the heart of Skinner’s experimental methods, and he was never an advocate of aversion therapy. While Burgess and Skinner disagreed on the questions of free will and the primacy of the individual, there is a strong element of caricature in Burgess’s representation of Skinner’s thinking, which was fundamentally optimistic and utopian. A careful reading of Walden Two and Skinner’s non-fiction works reveals more complexities than Burgess was willing to acknowledge.

Find out more

Walden Two by B.F. Skinner (affiliate link)

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (affiliate link)

The Complete Enderby by Anthony Burgess (affiliate link)

The Clockwork Testament in The Irwell Edition of the Works of Anthony Burgess (affiliate link)

Buying books from the Burgess Foundation’s affiliate bookshop (powered by Bookshop.org) supports our charitable work.

Listen to our podcast interview with Ákos Farkas, the editor of The Clockwork Testament.

This is such a fantastic deep dive into Burgess's philosophical fight with Skinner. The way Skinner's positive reinforcement framework gets conflated with the Ludovico treatment is somthing I've seen happen in discussions about A Clockwork Orange for years, so its nice to see that nuance acknowledged here. Freedom as choosing between good and evil rather than just having options at all is lowkey the crux of so much dystopian fiction.

I wonder whether Burgess ever read or wrote about The Blithedale Romance, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel which fictionalizes the failed utopian experiment of Brook Farm - of which he was an unlikely participant. It’s been a while since I read it, but the central theme if I remember it right had to do with the idea that any heavily ordered society, no matter how well-intentioned, is at odds with the wilder, more creative, more passionate aspects of human nature and is doomed to failure. Do you know if Burgess ever wrote about it, or about Hawthorne?